Kat Rosenfield deserves to be a syndicated advice columnist. So much good stuff here that people could benefit from.

Kat Rosenfield deserves to be a syndicated advice columnist. So much good stuff here that people could benefit from.

Mr. Ponnuru and Prof. George,

I read your article in the National Review with great interest because I’ve been trying to resolve the ethical dilemma of voting this year, and have so far been mostly unsuccessful. I am leaning a direction that is unfamiliar to me and I’m looking for a strong argument against it. I was hoping that your article would help me resolve this tension, but you did not address the argument that is leading me, as a lifelong and dedicated adherent to a pro-life ethic, to vote for Joe Biden. Here is that argument:

a. I do not believe that if President Trump returns to office next year that this will result in a substancial restriction on abortion availability or a reduction of actual abortions. b. I do believe that it’s more likely that a Joe Biden presidency will, in fact, result in fewer abortions. By that logic, I feel ethically bound to vote for Joe Biden, even though I oppose his actual position on the issue of abortion.

Here are my reasons for (a):

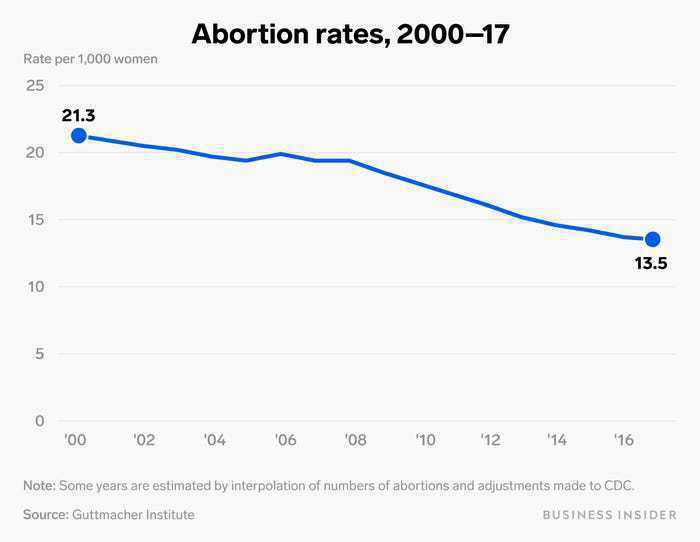

The abortion rate actually decreased under President Obama more than it did under President Bush! So it’s possible that had John McCain, an opponent of abortion, won in 2008, more abortions might have actually occured. I found it difficult to find more up-to-date data to be able to see how this trend performed under President Trump these last few years, but I feel like if it had shown a sharp drop in the abortional rate beyond the overall national trend, it would be heavily publicised by his supporters.

This leads to my reason for point b: namely that one of the predominant reasons women who get abortions say they do so is because they believe they cannot financially afford to have a baby. If Joe Biden, as expected, is able to strengthen social welfare programs, then this reason would have less salience, and logically lead to fewer women having abortions.

I am ardently pro-life, but I’m not convinced that voting for President Trump will actually achieve the result I’m most concerned with: the reduction of the number of abortions performed in the US.

Thank you for your attention and for your thoughtful article. I know it would be a lot to expect a response, but if you are inclined to tell me where I’m in error, I would welcome it.

8 Works of Fiction Every Christian Should Read

The four of these that I have read are among my favorite all time books, so I suspect that I’ll find the other four to also be worthy. This sparked me to find/buy a used copy of the Folio Society’s edition of Jane Eyre.

theconvivialsociety.substack.com

What Do Human Beings Need?: Rethinking Technology and the Good Society

Consider for a moment a more concrete and contemporary example. Why does anyone need a Ring camera? Or, better, whose interests are best served by a Ring camera? The most obvious answer is Amazon. If there is a problem that Ring is supposed to solve it is the problem of packages being stolen from people’s front porches, a problem that arises when our consumption is increasingly funneled through Amazon. But, of course, Ring presents itself as more than just the surveillance arm of a multibillion dollar corporation deployed to your front door. It hijacks the human need for security or safety and transmutes it into a need for Ring. It is chiefly the needs of Amazon that are being met, particularly given the way that Ring allows Amazon to also profit from partnerships with police departments. And as Illich would have readily predicted, this dependence on a corporate product comes at the additional cost of alienating neighbors, eroding social trust, and replacing mutual interdependence with a state of perpetual suspicion.

I have really missed the chance to chat briefly about your sermons at the end of the service. I’ll try not to make up for six-month’s worth of e-church all in one email here. I did have some thoughts though that I’d like to run by you if you’ll indulge me.

I really appreciate your effort to dial down the political temperature at the start of your sermon. Between your words on Sunday, and those of a neighboring church two weeks ago, I am very happy to be a member of a church that stresses unity within the body of Christ, the sovereignty of God, and human sin as the root of evils in society. “The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either – but right through every human heart.” (Alexander Solzhenitsyn) It appears to me that this has to be the foundation of a Christian understanding of politics to prevent it from taking an inappropriately large role in our hopes and priorities.

But we also need some principles I think to keep it from taking an inappropriately small role. Maybe this is just a problem that we might wish we had rather than an actual problem. But I wonder if a minimization of politics for a Christian might result in participating primarily along the same lines of identity and partisanship that over-prioritization does, since it doesn’t necessary give a Christian a reason to thoughtfully and purposefully engage. Certainly a very small view of politics will probably inspire less anger and rancor and so is preferable in the end, but I do think that will fall short of the faithful stewardship of our government to which I believe God calls citizens of a democracy. So the question that follows from framing politics in its rightful place (as you did) is, I think, “How can I love God and my neighbor through my participation in government?” Considering there’s a whole field of political theology that seeks to answer this question and others that stem from it or or adjacent to it, I certainly wouldn’t expect you to go down this road to introduce your sermon, but it does strike me as a useful way to frame a Christian voting ethic.

Speaking of anger and rancor – I think you are right on in categorizing anger as a result of unmet expectations. But I wondered about your criterion for judging anger as the “reasonableness” of the expectations. You gave the example of it being unreasonable to expect a believer to act like an unbeliever, which is very true in many ways (that I should not feel anger an unbeliever living a gay lifestyle makes sense to me.) But then is there no basis for anger directed toward injustice? And what is the alternative? We can certainly feel sad toward injustices like abortion or Uigur genocide, or human trafficking, but sadness is usually a fairly passive emotion and difficult to harness toward productive engagement. But, by your standard, why would I expect anything different from sinful humans? Can a victim of abuse rightly feel angry toward his abuser? Might that anger not be a necessary step on the road to forgiveness in that there is no forgiveness without first an acknowledgement of the truth that one has been wronged? Even for God, forgiveness follows wrath (Eph. 2:3-5) But if one’s anger toward that wrong is negated by “appropriate expectations”, then it feels like this leaves such victims in a state of denial and arrests any healing that could be achieved.

I apologize if I’ve taken any of the ideas in your sermon to places that they didn’t really need to go. I really appreciated the way you took us down the trail from “hear” to “put away” to “receive” to “do”. And even that you are preaching James. It’s been a long time since I’ve heard the book preached and have really enjoyed it these last few Sundays.

Gratefully,

The framing of the #1619Project remains the same today as when we published in Aug. 2019: We acknowledged 1776 as this nation’s official founding but asked readers to imagine what it would mean to consider 1619 as our birth year. That text hasn’t changed. https://t.co/w3tdtl9ZY5

— Ida Bae Wells (@nhannahjones) September 24, 2020

It was obvious that the 1619 project didn’t just ask readers to consider this as an “alternate history” thought excercize, but rather to consider the proposition as a more legitimate and accurate characterization of the founding of the United States.

And the project argues, effectively I think, that IF 1619 were considered to be the birth year of the United States it would result in a conception of a country whose very existance is molded around an inextricable core of black subjugation. There would be, by this reckoning, “no way out” aside from a “refounding” of the USA (a la Evo Morale’s refounding of Republic of Bolivia as The Plurinational State of Bolivia in 2005). However, it appears now that Ms. Jones disavoys that her work claims that the founding SHOULD be considered to be 1619. So if her characterizations are predicated on the founding being considered to be 1619, and now she claims that she isn’t arguing that we should consider that founding date to be actual, but only hypothetical, than her characterizations are also obviously not actual either. Which makes me ask, why would a school curriculum be designed around them? What good are they at all?

Surely the Democrats know that Amy Coney Barrett is a trap. After all, there is plenty of analysis that says that it was the public reaction to the Kavanaugh hearing that allowed the republicans to keep the senate. Nothing will turn out disaffected Republicans like seeing someone so relatable and and well-liked get smeared for her religion. Of course, failure to do this could suppress democratic turnout (though I think the democratic enthusiasm to vote against Trump is high enough this this would be a lesser effect.

Of course, this calculation would require restraint, long-term thinking, and self-sacrifice on the part of the democratic senators. Therefore, I think it’s unlikely.

In response to this review. (Also, so strange for somebody to go from this to that review. I mean, he acknowledges in the review that his mind has changed on the book, but the initial response is just SO effusive that it seems like there is something more going on.)

Dr. Robinson,

I appreciated your lengthy treatment of Freddie’s book, but disagree with you about what is possible within constrained resources. Even given your conclusion that everybody could achieve at a high level if they are given what they need for their learning, no conceivable education system could give every child exactly what they need. Any teacher will be able to tell you that every student’s learning profile is unique, not only their interests, but all across different academic abilities. Even the most ambitious conceivable system for equitable education provides shared environments and experiences that are going to be more advantageous to some than to others. Even in your example of the cactus and the orchid, it may be possible to improve both of them somewhat, but if you really want the cactus to take off, you’ll need to reduce the watering, which will then create an opposite inequality. The maximum number of students that a high school teacher would likely be able to completely individualize a curriculum for would probably be about 25 (even this would be a stretch). The system would need to expand its workforce at least sixfold (high school teachers today usually have a student load of around 150). In Florida today, this would mean that 5% of the population would need to be employed as teachers.

The conclusion that we can achieve this kind of equality of outcomes is not only unrealistic, but it’s disrespectful of the dignity of individual differences. Not every Slow Sally will go into philosophy. Maybe her challenge in Chemistry isn’t that she needs the philosophical questions answered, but that she dislikes the experience of the effort it takes to focus on several concepts at once and relate them in her mind. I’m sure you have met or known people like this – who just dislike the mental discipline of thinking carefully about complex matters. This, in my opinion, points to the root problem the cult of smart has created for our society: that we attach a moral valence to this temperament.

I’m sure with the right training and effort I could be a triathlete, but I find that kind of physical exertion to be unpleasant to the extreme and would be resentful of any system that demanded or shamed me for not achieving that level of athleticism.

This note has become slightly longer than I intended it to be. I do want to reiterate my gratitude and appreciation for your work, as it has required me to think through Freddie’s argument again and test it against your critiques. However, I’m not convinced that it doesn’t stand on its own against them.

In solidarity,

In response to this newletter posting: America’s Systemic Racism Conspiracy

Mr. Erickson,

I really appreciate your thoughts on the subject and for pointing me to the followup on the story of the disappearance of Franck’s article. I also think you are right in many of your prescriptions for what the church should do. However, I’m concerned that the phenomenon that we see on the left of “Trump derangement syndrome” is also occurring on the right of “SJW derangement syndrome.”

I’m referencing here your paragraph,

Therefore, churches are left to do what exactly?

Work with those on the left who reject Christianity to enact public policy solutions that are devoid of Jesus, implemented by sinners who do not recognize systemic racism as a sin, and fueled by a moment that sees everything as an allocation of power?

Good luck with that.

Dismissing the possibility of the church working at all with leftists to bridge the racial divide only cuts off an avenue of potential unity, cobeligerancy, and solidarity. While we won’t be able to affirm everything that “antiracists” believe, I think that we should be able to find common ground on the idea of racism as “sin”, even though we will disagree on the theological implications of that. The doctrine of common grace should lead us to recognize that public policy solutions that lead to prosperity, flourishing, and justice for all (or at least more than currently can access it) is never divorced from God’s mercy on his creation, which finds its full expression in the person and work of Jesus. And while believers should never see the allocation of power as a totalizing lens, it should certainly be an aspect of how we view the world, because the corrupt wielding of power over one other is one of the corruptions of the fall that we should both lament and rebuke.

The reason I am taking time to submit this to you is that I believe that the loss of any sort of common ground between orthodox Christians and left-leaning Americans will annihilate the witness of the church to this population. The church must be a distinct witness separate from rightward politics, and the issue of race is one where I see the attitudes of many on the right to contract the Biblical narrative and teaching much more sharply than those held by many on the left. To me, this is an opening to build bridges.

Thank you.

Movies my kids will probably watch, if I have anything to do with it:

in fact, the secret ballot is a latecomer in American political culture. It isn’t really adopted - the first presidential election where the secret ballot is the preponderant mode of voting is 1896, which is also the first presidential…

GROSS: Wow, really?

LEPORE: …First presidential election where some is not killed on Election Day. No, voting in public is far more ancient and more American in that sense. So the whole idea of being a good citizen requires publicly exercising your franchise. So people - you go to the polls and you would - the government didn’t supply a ballot. You would - you know, first you’d have to - first, they were all viva voce. You’d basically be like a caucus. You’d go to the polling place and be like, OK, if you are voting for Smith, stand over here against the butcher’s. And if you’re in favor of Jones, stand over there down by the library. And that’s how the votes were made. And the polls would be counted. That - poll means the top of your head, so people would count the tops of people’s heads, and that’s why it was called the polls (laughter).

So the call to reform public voting, or what was known as open voting, was super controversial because - Massachusetts was the first to do it. And they had this idea that the government would supply these envelopes, and you could bring - so people would start - when the party system got really strong, and newspapers were partisan, like, the Republicans would print a ballot - like, a whole party ticket. It would be, like, we’ll say it’s red. And the democratic newspaper would print a blue party ticket. And so you’d go to the town hall - this is when oral voting had kind of been replaced by paper voting because people were literate. But still, you’d have this giant, long sheet, like a railway ticket, like two-foot long. It would be brightly colored. And so people would try to prevent you from getting to the ballot box and casting your vote. The parties would hire these thugs to go down there. Democratic thugs, you know, would beat up all the Republicans with their blue tickets and prevent them - but people would die.

People were killed every election (laughter) in these incredible battles over trying to get to the - then there was this thing called vest-pocket voting. So this was a little bit sneakier. If you wanted to keep your vote private, you’d fold up your long, you know, blue ticket, and you’d stick it in your vest pocket and try to get to the polls without anybody, you know, knocking you on it. But this was considered unmanly. So when Massachusetts in the 1850s tried to say, well, we’ll just supply envelopes and people can put their tickets in the envelopes before they come to the ballot box, it was repealed because people said that only cowards would use an envelope to vote, you know. So it was a really controversial thing. It takes years for the secret ballot to be adopted, and it’s part of, actually, a lot of forces that are not - people wanted to - didn’t realize there was a lot of corruption as a result. All kinds of party machine nonsense - people are being beaten up, you know, that’s obviously not good. Also, women wanted the right to vote, and they were like, we wouldn’t need to vote in secret. We don’t want to get hit in the head. So suffragists were sort of supporting the secret ballot. And it was first passed in Massachusetts and New York in the 1880s.

But then for years, the only other places that adopted the secret ballot - which is a written ballot supplied by the government to each voter - was the South after Reconstruction because it was a way to disenfranchise newly-enfranchised black men who - none of them knew how to read. I mean, they’d been, you know, raised in slavery, lived their entire lives as slaves on plantations. And so it was - the real success of the secret ballot as a national political institution had to do with the disenfranchisement of black men.

GROSS: So the secret ballot was a way of helping them get the vote.

LEPORE: No, it’s helping - it was preventing them from voting. If you could cut your ballot out of the newspaper, and you’re going to vote a party ticket, and knew you wanted to vote Republican, and that ticket was going to be read, you didn’t have to know how to read to vote. Immigrants could vote. Newly-enfranchised black men in the South could vote. It actually was a big part of expanding the electorate. But people in the North were like, hey, we don’t really like when all those immigrants vote. And people in the South were like, we really don’t want these black guys to vote, so they, in a sense, kind of colluded over - and there were good reasons for the secret ballot too. But they - very much motivated by making it harder for people who were illiterate to vote. It’s essentially a de facto literacy test. And so…

GROSS: Because in the polling place - like, in the election booth - it wouldn’t be, like, code-colored like that, or you couldn’t ask anybody to read it to you. Is that what you’re saying?

LEPORE: You couldn’t - right. And so there’s some counties in Virginia, I think it is, that in the 1890s they print some regular ballots. But then they print ballots in Gothic type - like, deep medieval Gothic type. And they give all those ballots to the black men. It’s a completely illegible ballot. So there’s a very - so anyway, people did - people debated it a lot of the time for those reasons, and also - I mean, if you think about it, why does Congress vote in the open? Well, it could be if you’re a congressperson, your vote should be known to the public. That’s part of transparency that we believe in, and it seems obvious to us. People believed that way about ordinary citizens voting as well for a long, long time. So the caucus in Iowa, that method which is so kooky and kind of fascinating - that’s deliberative democracy. That is a certain kind of exercise of civic virtue that needs to be conducted in public.

GROSS: So I am stunned by everything you have just told me because I thought the secret ballot was one of the principles American democracy was built on. Did you always know this did you find that out later in life?

LEPORE: No, I totally didn’t know. I always have to find things out because I just get curious about them. Remember the election with the Florida ballot - the hanging chad and everything? So I was asked to write a piece about voting machines or technologies in voting because we were looking like we were maybe moving to Internet voting. And I thought, I don’t know if that’s - going from paper voting to Internet voting doesn’t seem that big of a deal, but what’s a really big deal would be going from oral voting to paper voting. I wonder what that was like. And so then I did all this research and realized that, oh, the secret ballot is just such an incredible latecomer. And it’s - the whole story of its origins utterly shocked me, and was really illuminating because it made me think about how Victorian our voting is. Do you know what I mean? It’s like, go in this little booth with a little curtain, and you’ve got to be alone, and it’s going to be dainty and private. It is actually a kind of Victorian domestic, quiet, sacred, middle-class space. And that was carved out by middle-class reformers, you know, against the kind of hurly-burly of, you know, the rowdy, exciting, drunken voting day.

Currently reading: The Cult of Smart by Fredrik deBoer 📚

I learned about this book listening to Jesse Singal and Katie Herzog’s highly entertaining and sometimes insigntful “Blocked and Reported” podcast. Jesse did a pretty extensive interview with Freddie deBoer. I’m still in the early pages of the book, but here is the gist of it based on the interview and the first quarter of the book:

Academic achievement and accomplishment is prized about all else in our society today. It’s the source of both prestige and leverage for economic advancement.

It’s long been claimed by the establishment that academic achievement and accomplishment are inhibited primarily by structural inequalities and institutional mediocrity within education, or by a lack of will or self-confidence on the part of particular students. The solutions being enacted are to “fix” education and to inculcate within students the belief that they can accomplish anything by virtue of developing the work-ethic or “grit” to follow through with whatever goals they choose for themselves.

I think it’s worth lingering a moment on the notion of “fixing” education, because Freddie is quite persuasive when he describes the way that education isn’t primarily broken due to a lack of accountability, laziness, or structural racism, but because it’s being tasked with accomplishing two diametrically opposed goals: to be an engine of equality (meaning the advancement of the underpriviledged toward equality with people with priviledge) and a system to sort students on the basis of their merit, as measured by academic achievement. Logically, it’s impossible for any institution to do both of these things, and the better it accomplishes one of them, the more ineffective it will be at the other.

Freddie claims that the most significant inhibitor of academic achievement is innate academic ability. However, discussion of this is a political and institutional third rail. Freddie has forshadowed that he’ll go into some discussion of the evidence that genetics is the most reliable determinant of academic ability. I haven’t read any kind of discussion of this topic before, so I’m quite looking forward to seeing the argument he puts forth here.

This book has captured my attention because it is very well aligned with my frustrations as a teacher. The standard for academic achievement to graduate high school has been pushed higher and higher over the last twenty years. Last year I decided to take the FSA (Florida Standard Assessment) for myself to see what it would be like for my students who were trying to pass it, and was taken aback by just how rigorous it was. Several of the reading passages and question sets were ones that I would certainly have been puzzled by in high school. And, not to brag, but I earned a perfect score on the reading portion of the SAT when I took it in 1999. Indeed, if I hadn’t learned in college of the relationship between Romeo and Juliet and Pyramus and Thisbe college, I would have been completely stymied by one question set. The expectation that all students must be able to perform at a very high academic level in order to graduate is in ascendency in the state education system. Indeed, it seems like the goal is for all high school graduates to be “college ready” with this assessment being the primary accountability measure. So where does this leave students who do not have the ability to succeed in college? In misery. Day after day they struggle through classes that are trying to help them achieve at level beyond their abilities and they are told that their failure to be successful is that they aren’t trying hard enough. What a nightmare. And teachers are also told that their students’ failure to be successful because they aren’t trying hard enough. Or are incompetent. Or don’t really care about their students. Or harbor unconscious bias.

Not great for morale.

The book is provocative beyond just its discussion of education though, because the entire economic organization of society is predicated on the notion that education is the pathway to advancement, and the fairness of that system is reliant on our efforts to give all students an equal shot at success. But if success is going to be mainly determined at the end of the day by innate talent, then all the leveling of the playing field will do is create a different set of winners and losers, where again the losers find themselves in that position by no fault of their own. How is that a just society?